Making hackathons more inclusive

Hackathons are great, they do however exclude people! I created a plan for a hackathon to include people who may normally be excluded from taking part. Encouraging people to understand the problem through research. Offering training and up-skilling for those who are not confident in coding or design.

First we need to define our problem statement and frame it for a common understanding between organisers and participants.

Use the following method to understand the problem(s) you’re trying to solve. If you don’t have a clear and simple answer for each category — then work towards clarifying that statement before moving on.

🏆 Goals

Do you know clearly what problem you’re trying to solve and what you’re working towards?

if yes then:

🤔 Understand

Do you know the biggest problem you face?

if yes then:

🖼 Frame

Can you articulate your idea simply and clearly?

if yes then:

💡 Ideas

Do you have a range of ideas on how to solve the problem?

if yes then:

⚖️ Evaluate

Have you evaluated the ideas? Are they robust? Which idea is the strongest?

if yes then:

🙌 Decide

Test and choose the strongest idea, having a clear vision will ensure an effective solution

Using the above method will give you a clear direction that’s understood by everyone. For this example I decided to focus of mental health.

Problem statement

In the United Kingdom, mental healthcare services are in greater demand than ever.

One in four people will experience a mental health problem at some point in their lives.

(That’s a lot of people.)

Mental health conditions are increasing worldwide, with a 13% rise in the last decade up to 2017. WHO claims that around 20% of the world’s children and adolescents have a mental health condition. Suicide is the second leading cause of death among 15–29-year-olds (Mental health, n.d.).

The two most common mental health conditions, depression and anxiety, cost the global economy US$ 1 trillion each year. However, despite these figures, the global average of government health funding for mental health is less than 2% (Mental health, n.d.).

Healthcare systems and institutions are struggling to keep up with this increased demand, only providing, limited, acute and reactionary care; this approach is not well suited to the rising numbers of mental healthcare patients and an aging population that requires more preventative and long-term care.

To create a collaborative and knowledge sharing hackathon to solve mental healthcare service access problems for patients.

To raise awareness of robotic process automation (RPA) as a possible solution to a technical and non-technical audience.

If hackathons want to encourage delegates to develop or improve skills to contribute in approaching existing gender bias in computer science, the hackathon would need to provide incentives or materials for personal skills development rather than foster an environment that favours proficient skills utilisation (Richterich, 2017).

This hackathon plan aims to enable delegates to collaboratively solve with RPA, automation and AI to solve problems for the limited resources of mental healthcare solutions in the NHS.

Some example problems found by patients in the UK:

25% of patients have to wait for more than three months to see a specialist.

6% of patients have to wait for more than a year to see a specialist.

(Campbell, 2018)

Rather than using the hackathon as a competition, the intent is to educate delegates in automation, in particular, Robotic Process Automation (RPA), and to encourage collaboration towards the shared goal of solving patient access to mental health services. Rather than separate teams formulating their CV Driven Development (CDD) goals towards a largely unfinished and unusable product at the end of the hackathon. CDD practice prioritises design and development choices enhancing individuals Curriculum Vitae over other potential solutions, regardless of the end-users needs (Jee, 2015).

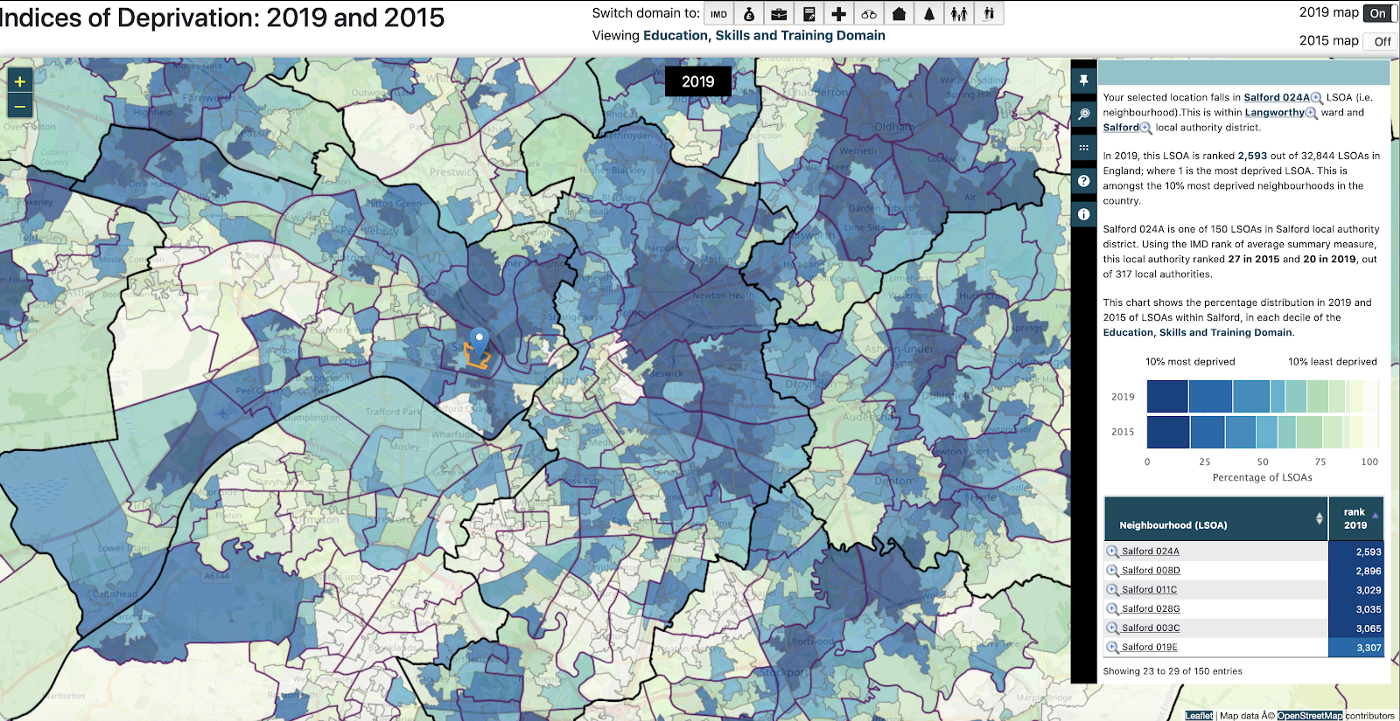

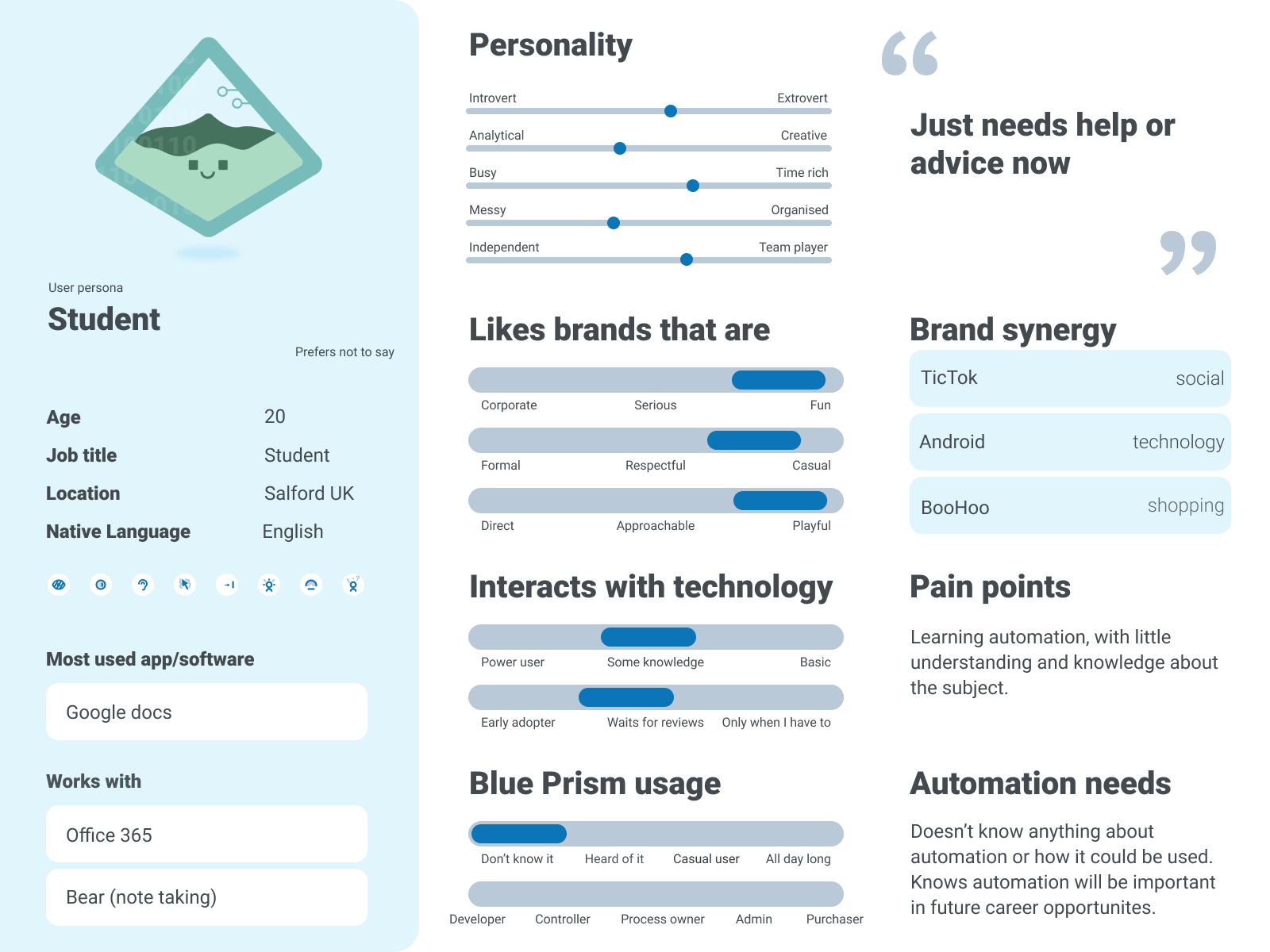

To address diversity inclusion part of the delegate recruitment campaign will target colleges and universities in skilled and economic deprived areas, using Indices of Deprivation 2019 local authority dashboard. The maps reveal local authority data within England concerning income, employment, education and skills (English indices of deprivation 2019: mapping resources, 2019).

Fig. 1, Education, skills and training data, focused on Salford UK, from http://dclgapps.communities.gov.uk/imd/iod_index.html

Introduction

Hackathons are generally techno-creative events where delegates form teams in a physical location (Richterich, 2017) to solve a problem statement or brief defined by the organisers. Hackathons are generally competitive, with teams competing under the confines of limited time pressures for incentives such as prizes (Richterich, 2017).

The conventional aim of a hackathon is for teams, or individuals, to practice collaborative software development. The first time the term ‘hackathon’ was used to describe an event gathering volunteers software developers working together on an open-source operating system, OpenBSD, in 1999 (Richterich, 2017).

What started as a collaboration on open-source software ( freely allowing the source code to be added to or used in a completely new way) quickly became adopted by organisations (Richterich, 2017). These organisations started using hackathons to gather innovation ideas quickly through sponsorship and competitive competitions. Hackathons swiftly gained a different focus from that of collaboration. To often ostentatious sporting arenas of technical prowess and perfect pitches where prizes can sustain annual incomes (Folz, 2015). Many organisations translate the values of a longstanding hacker subculture into new work normalities, socialising workers to innovate while institutionalising teamwork under time-sensitive pressures. Most important, hackathons reorganise workspaces and work time, using ceremonies of play and singular rewards to gain new product ideas or solutions to existing problems without offering participants full-time jobs (Zukin and Papadantonakis, 2017).

In his Medium post titled ‘Selling Out and the Death of Hacker Culture’ (2015), former hackathon enthusiast Rodney Folz explains:

“Hackers are expected to listen to hours of company talks before being allowed (allowed?!) to hack. There is a clear contractual transaction of goods and supply: your time, your résumés, and your intellectual labor in return for their dinner, their cheap sunglasses, and their shirts emblazoned with corporate logos (Folz, 2015).”

While this comment reflects Folz’s own experience, I too have experienced similar ‘contractual transactions’ where my expertise and attendance of hackathons have been comparable. Attending a hackathon at Microsoft, I had to listen to numerous talks about different Microsoft products. Speeches around the hackathon brief and lectures from sponsoring companies on best practices and how to innovate. While these talks were interesting, they were not what I was expecting, that I would, upon arrival, start hacking, collaborating and networking. This hackathon experience was more educational than participation, especially during the first two days. The winning prize of a £500 restaurant voucher (Barclays takes the crown at Digital Wallet Foundry, 2013) was the reward for five days of 12+ hours of participation and positive public relations (PR) for both Microsoft and Barclays. While participants of hackathons, primarily, do not attend for the prize. Participants connect with each other; to network with corporate representatives and potential investors; to understand their location in “the technology ecosystem” that partner with hackathon organisers. Participants are well aware of these opportunities and use the event to promote and advance their career by enlisting both self-interest and a collective enthusiasm in the hackathons ceremonial participation and engagement (Zukin and Papadantonakis, 2017).

Diversity in hackathons can be problematic and may lead to biased solutions. While the general entry to a hackathon is between Free and £30, other financial considerations for delegates to supply personally owned technology, such as high-spec laptops, mobile phones or other gadgets like sensors, circuit boards and even robotics, aid the participating teams to produce their prototype. This high monetary barrier to entry often precludes participation from areas of low-income homes or ethnically diverse backgrounds. As observed by Zukin and Papadantonakis (2017), in their article’ Hackathons as Co-optation Ritual: Socializing Workers and Institutionalizing Innovation in the “New” Economy’. Most participants of The Hearst Hackathon (New York, 2015) were visibly male (80 per cent), Asian (50 per cent), and white (40 per cent). They were between the ages of 18 and 35, and many turned out to be students.

Participants’ technology choices, from hardware to software at hackathons seem particularly relevant to a lack of diversity, since the utilised tools are by no means neutral but have techno-political implications. Postigo suggests that technology acts as an opportunity allowing ‘for a particular relationship between consumer and content’ (Postigo, 2012). Choices of hardware and software exclude users that don’t have access to them freely. Often hackathon solutions already include the biases, dependencies, investment toward gaining software engineering skills, corporate relationships and economic outlay equal to that of the participants before the event is undertaken.

While hackathons can present ‘opportunistic design’ in order for teams or individuals to win its coveted prize and ‘bragging rights’ to claim victory. Often due to time pressure a ‘Frankenstein’ solution, that of coping and pasting code from websites such as Stack Overflow is acceptable and often necessary. It should be noted that hackathon solutions are far from production ready and require examination into furthering gender and social diverse future techno-creative endeavours. If the host organisation(s) are anticipating a comprehensive product in return of investment for hosting, then they will be disappointed. What hackathons excel at is rapidly proving concepts or multiple ideas that can form the basis of future development.

Aims and strategy

for an automation and AI hackathon.

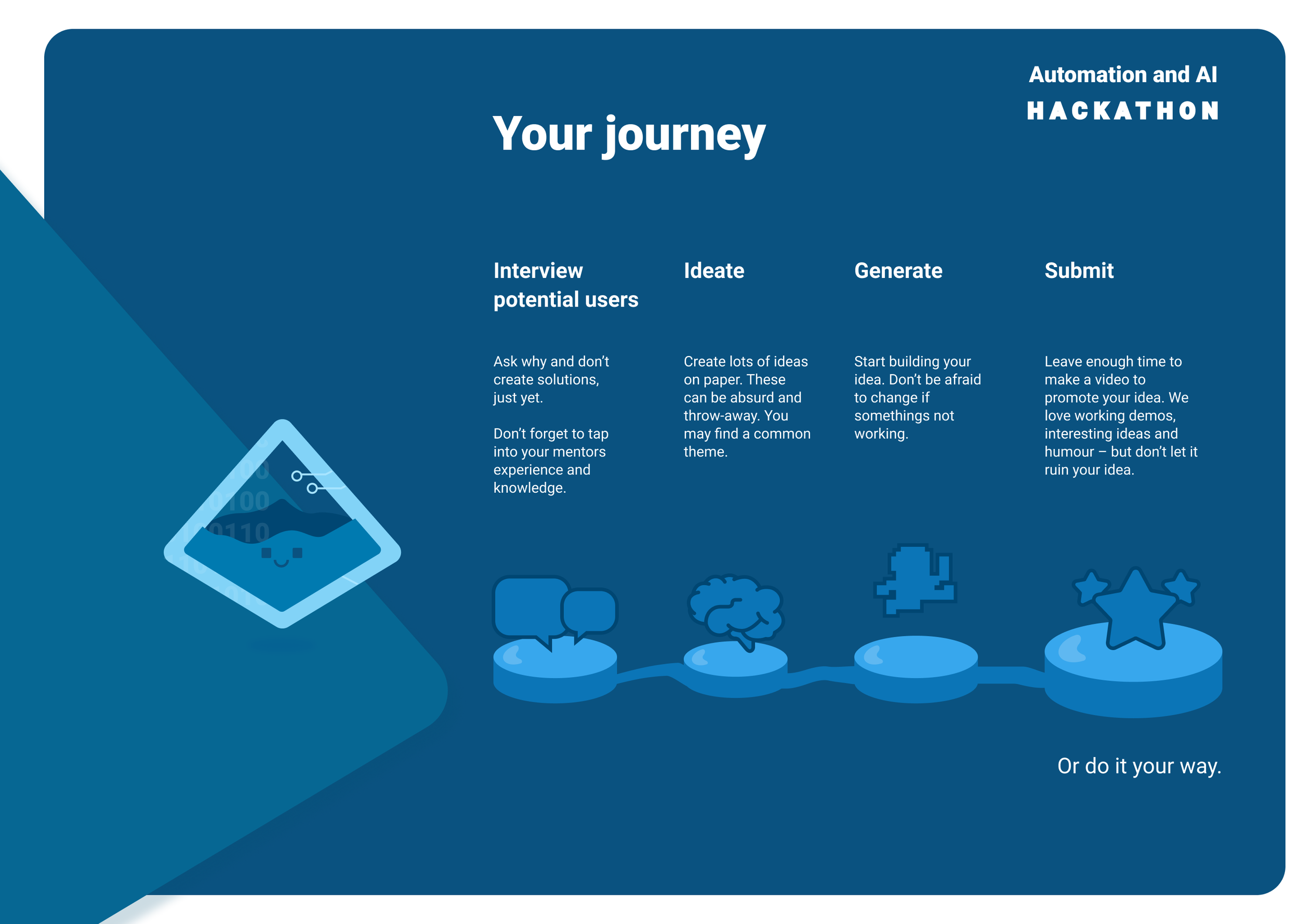

The aim is to create a hackathon where delegates collaborate to solve the brief. The hackathon should provide educational material to inform and upskill delegates rather than requiring highly educated or skilled entrants. To de-focus the hackathon as a competitive event, allowing delegates of highly skilled computer engineers and delegates with little, experience in delivering technology software or applications.

The hackathon proposes to apply distinct aims and purpose for the hackathon. The delegates, have to create an automated process (or skill), website, mobile app or software, film, animation or podcast that would meet the purpose of a brief.

The organiser (myself) and delegates expect to solve an identified problem within the theme of mental health, directing participants to create an output for a specific problem.

Recruit mentors and practitioners, both in person and virtually that will tutor delegates in creating an automated process. Having mentors and practitioners directs the hackathon focus to one of learning and gaining new skills as reward and recognition for engaging in learning at the hackathon delegates will be awarded a Blue Prism RPA entry-level certificate. Other awards issued after the submission deadline to delegates will avoid competitive payouts for winning teams and merit awarded for teamwork, participation and acts of kindness during the event. Acknowledging previous hackathon submissions and their winning entries are prototypes that are not usable, insecure or ‘gaffer-taped’, ‘smoke and mirrors’ solutions that do not serve as a complete end-to-end technology solution.

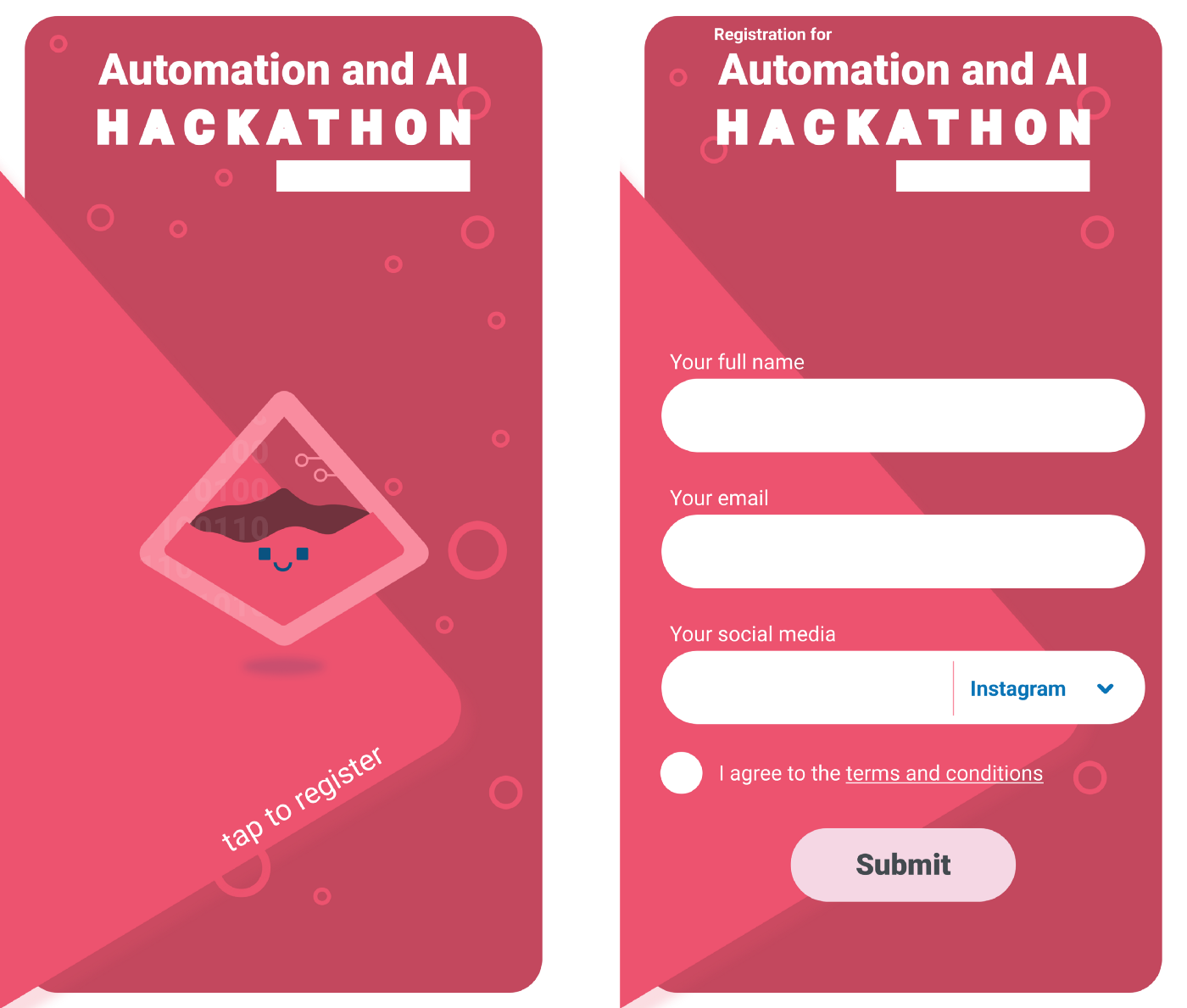

My previous experience of organising hackathons has dictated offering free tickets always leads to a large percentage of ‘no-shows’. To limit the number of registrants obtaining tickets and then declining, the hackathon will charge delegates for tickets. The hackathons entry fees are to be donated to mental health charity CALM. To address the often prohibiting skills, technology and cultural barriers of hackathons, I propose offering around forty per cent free tickets to eligible delegates from diverse backgrounds and low-income households. Delegates who apply for a VIP pass through this scheme will automatically have necessary software and hardware provided to them if attending in person. While the hackathon wishes to provide the same level of support to virtual delegates, it acknowledges that this would be unfeasible.

Recruiting paying delegates would be, primarily, supported through social media awareness, referrals and organisers networks, supported by a dedicated website where potential

delegates can find out more information and purchase tickets. Some social posts will have supporting material, for example, videos (Video creative artefact) and Podcasts (Podcast creative artefact).

To recruit diverse delegates using data from the Indices of Deprivation 2019 local authority dashboard, Fig 1 in the overview section of this document, explicitly targeting schools, universities and colleges in these areas. Coordinating with their existing methods of communication, such as student newsletters, see email artefact, University websites and posters.

Core communication strategy examples for the hackathon, page 17 onwards, illustrate the hackathon design styles, digital accessibility and tone of voice. In this section, I have described the research methods to question design decisions and the results. Through testing these designs and assumptions of typical personas to relate with delegates throughout various methods of communication.

Raising awareness before the event

To make any event great you need people to attend. For this hackathon I created a communication strategy, personas and tone of voice so that everything tied together to increase awareness from medium to medium.

Communication strategy

The aim of any communication for the hackathon should…

Promote the hackathon for the purpose of awareness, engagement and to encourage and increase recruitment.

Reach different audiences through audio Podcasts, multiple social media platforms, email and a web presence.

Align content creators using a tone of voice style guide to create consistent messages that talks to humans to engage them with hackathon updates, promotions and key messages.

Use consistent and accessible images, colours and design principles that include the widest possible audience. I’ve outlined the principles of accessibility as a deck of cards that can also be used by the hackathon content creators and delegates titled #NoUserLeftBehind.

Tone of voice for the hackathon

To define a common communication strategy I created tone of voice guidelines to help keep consistency across channels of communication.

👭 Humans

Talk to humans, not developers, designers or enthusiasts who already know what a hackathon is or by using technocratic specific language.

Create delight.

Inform don’t lecture.

Guide and educate.

Try to ask, don’t tell, pressure or preach.

Cater for different levels of expertise.

Humans don’t read large blocks of text, especially on social media — expect an attention span of less than 8 seconds.

Introduce familiar cultural references that can help to explain complex concepts.

Refer to people by their first name, be friendly, not overly friendly.

📝 Structuring readable information

Create bite-sized information, you don’t need to tell someone everything in one go.

When dealing with complexity use visuals that help explain.

Keep paragraphs to a minimum.

Always use sentence case, it’s a lot easier to read than Title Case and CAPITALS is shouty and even harder to read.

Never use italics!

Avoid using light and thin fonts, they make look cool but for some are impossible to read.

To split up information use En Dash (–) rather than a hyphen or minus (-).

Don’t use exclamation marks, unless you are conveying surprise or excitement — less is more.

Do not span text over large areas — like the entire width of a screen, this makes it really hard to read and follow.

Avoid centrally aligned and justified text, this again makes it harder to read.

When using abbreviations and acronyms — spell it out on the first use, for example, Artificial Intelligence (AI).

Targeting hackathon delegates

Using persona mapping and data to gather to formulate a campaign to the right audience.

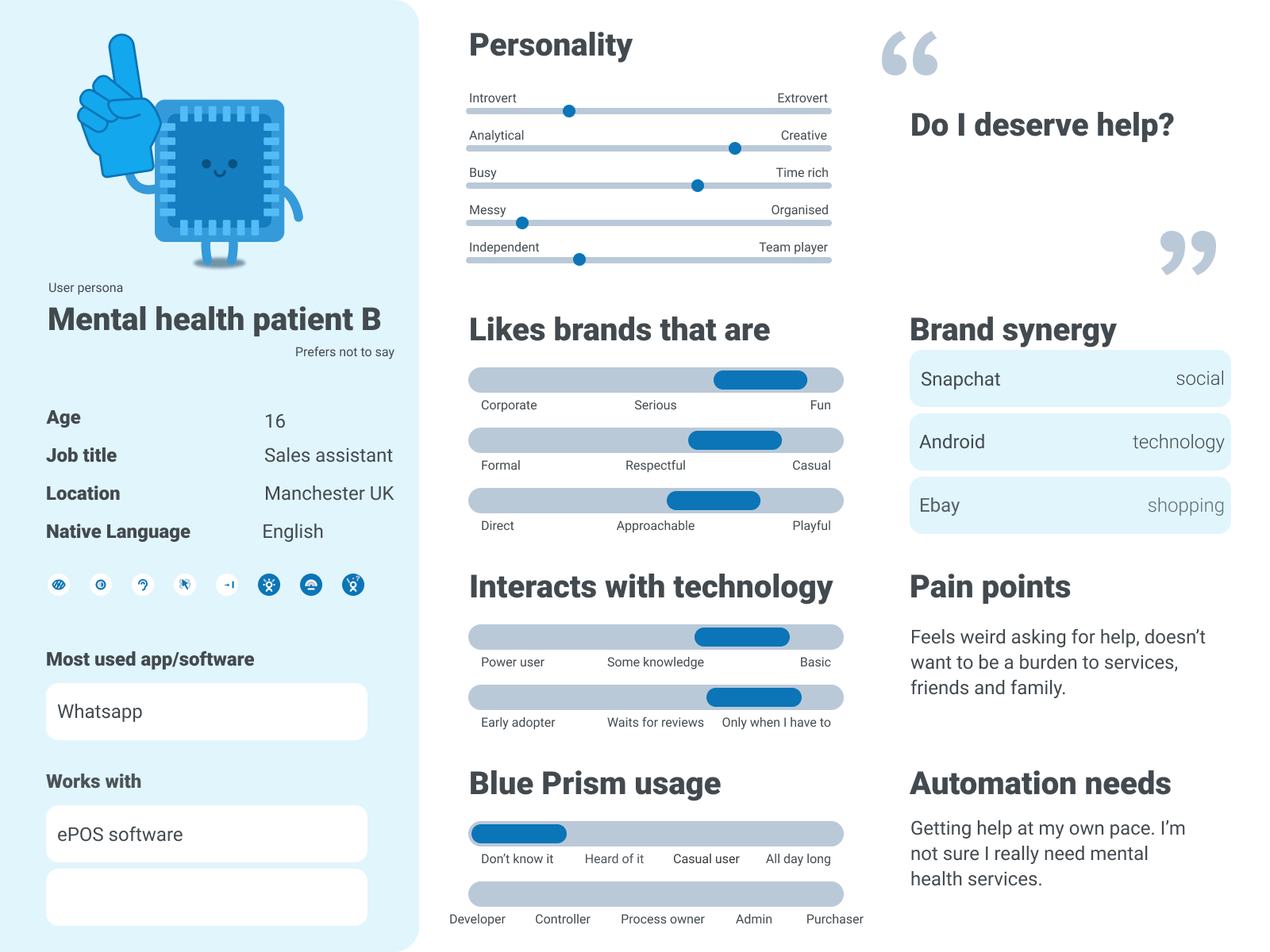

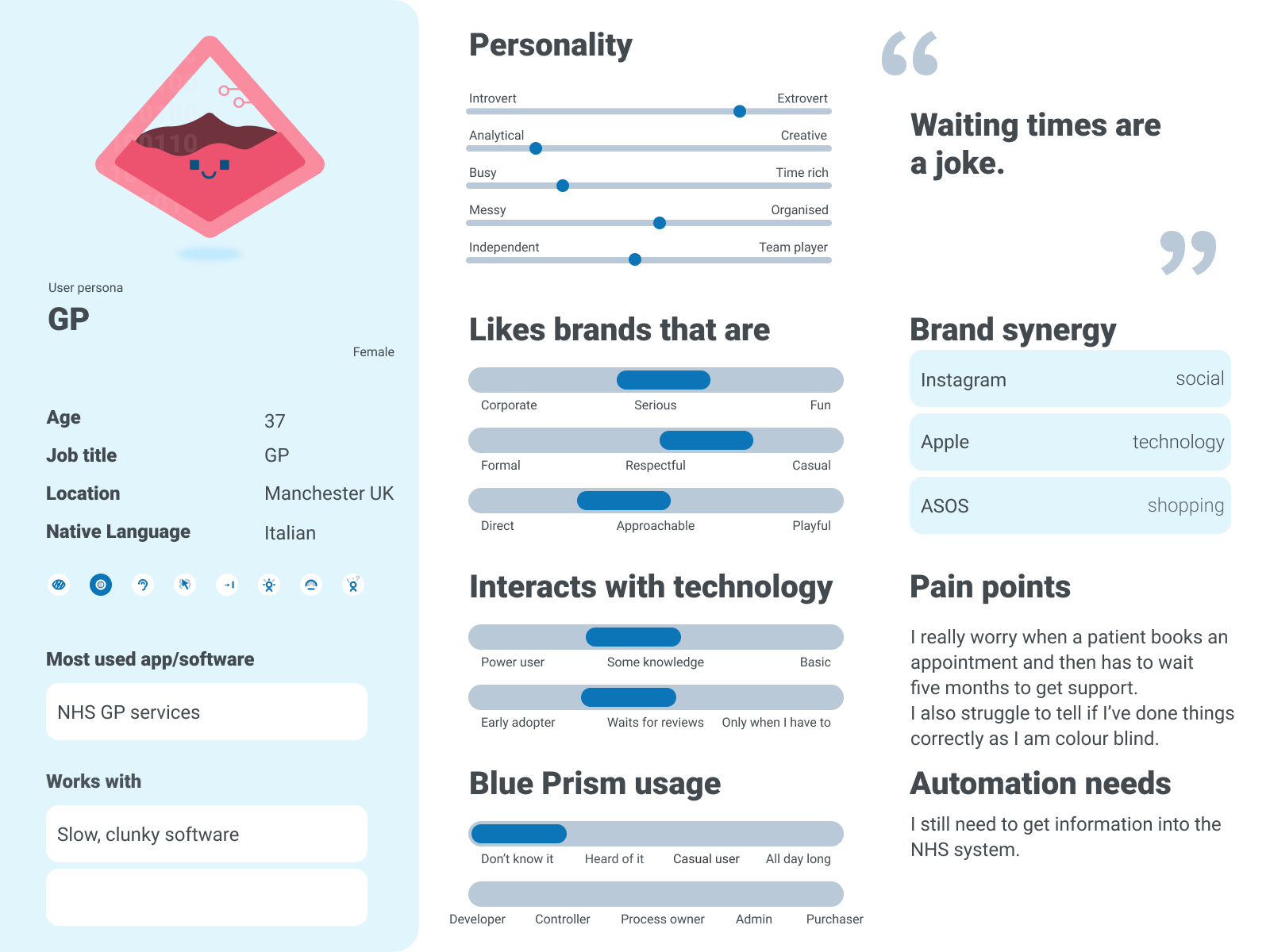

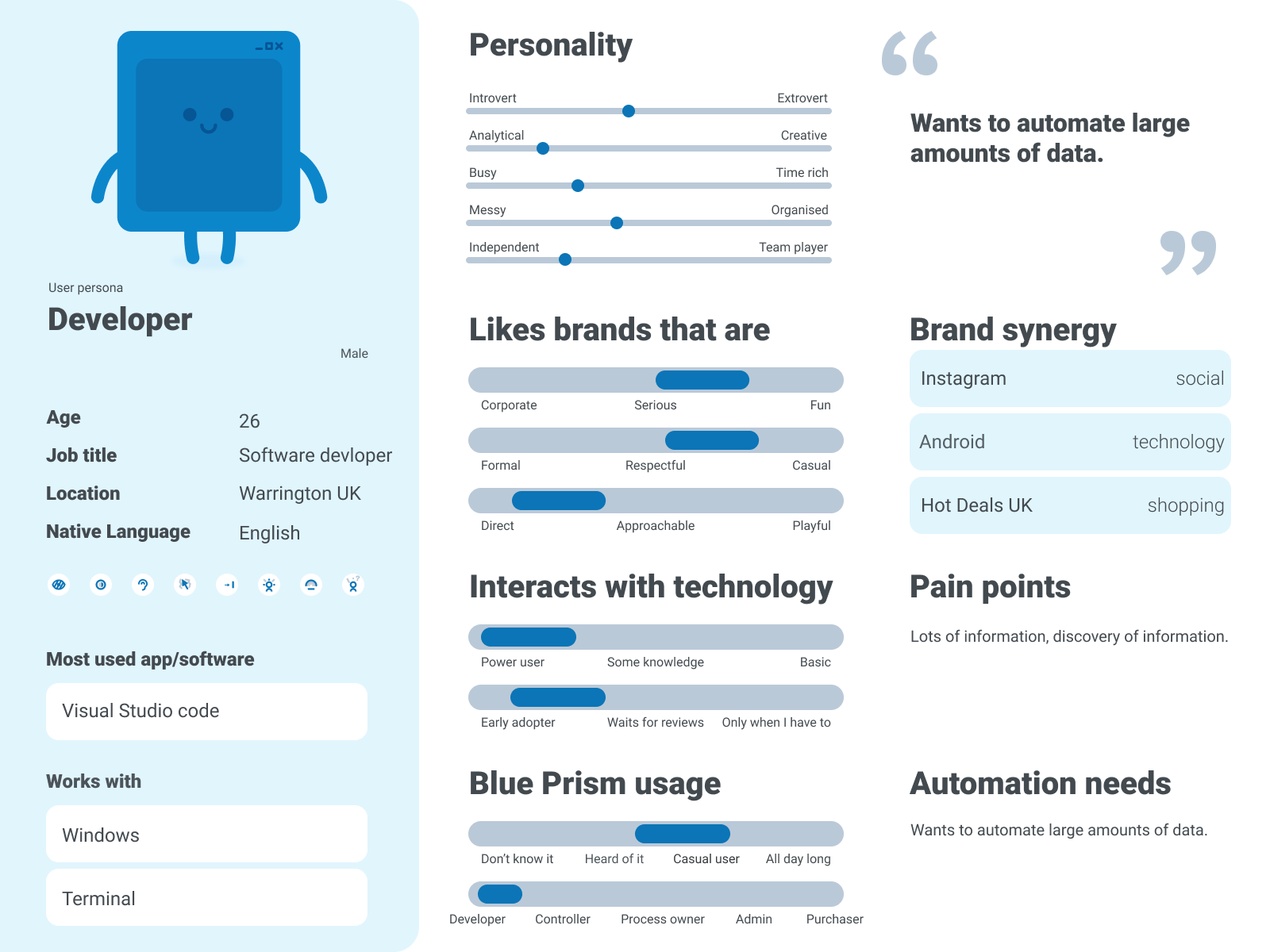

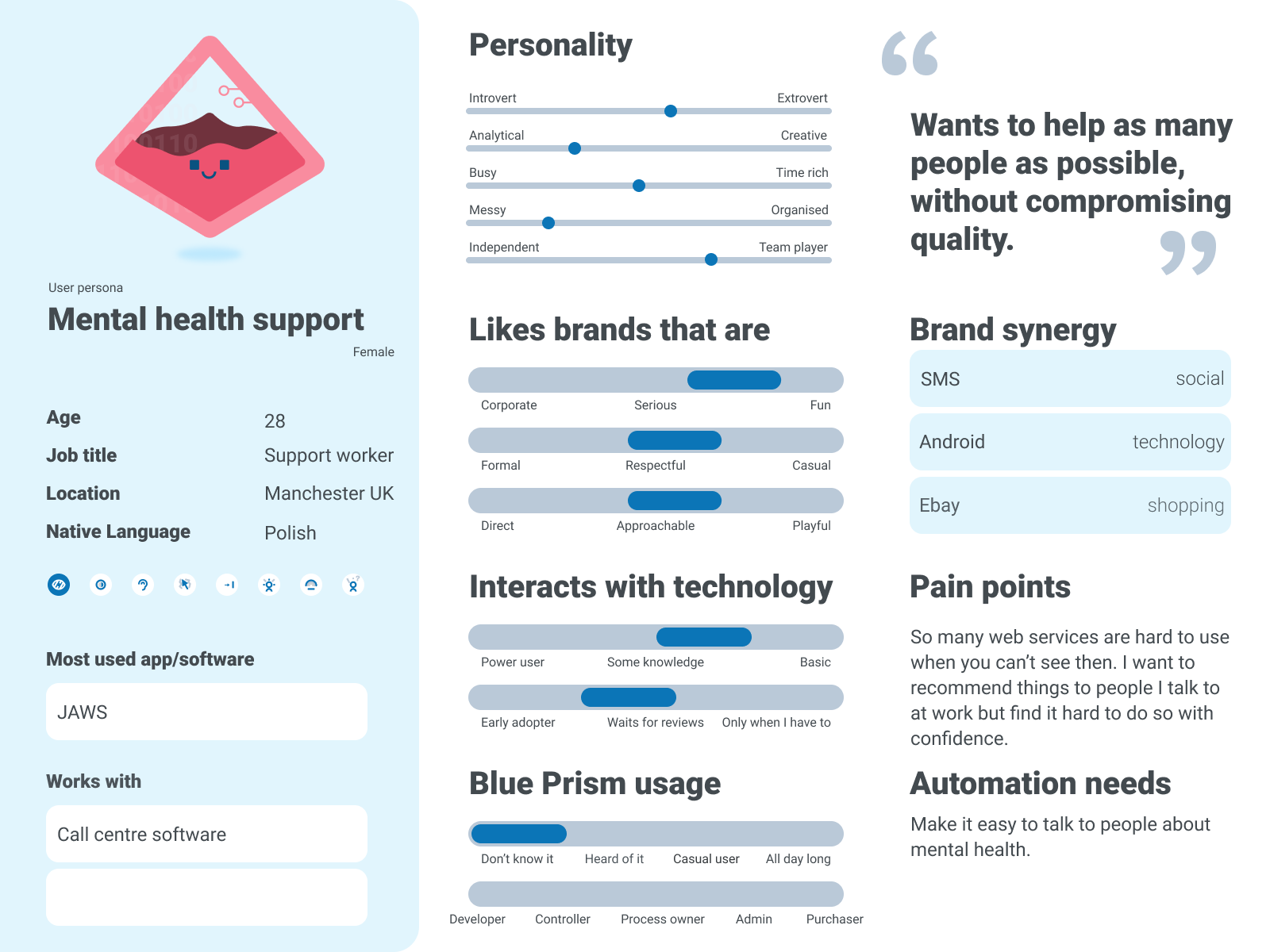

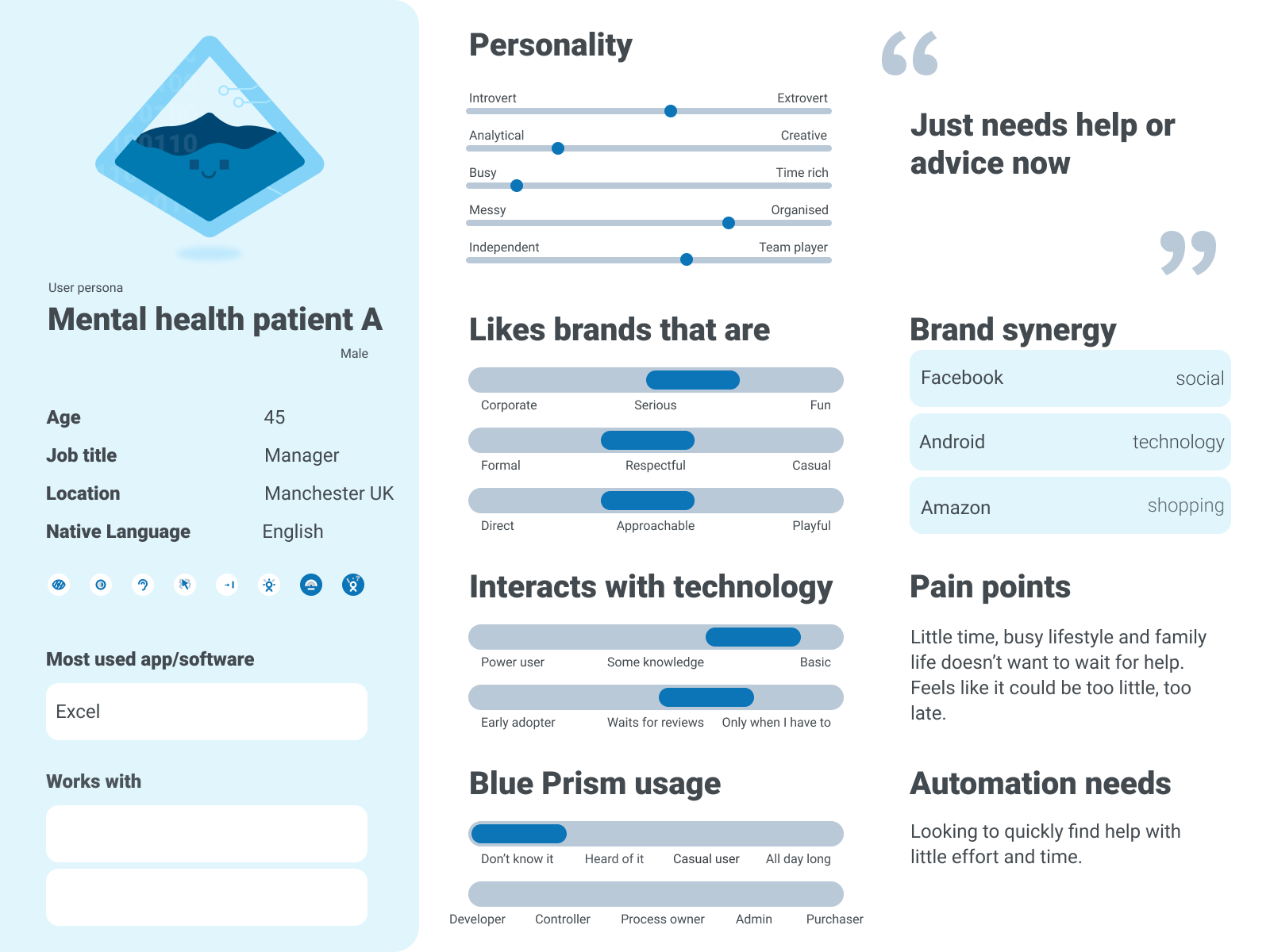

A target audience persona outlines a a member or group of members to target when creating a campaign. I have created fictional representations of my intended audience gathering their behavioral data, age, job title and personality traits, using the design thinking method of paired opposites. Creating personas allows for personalisation and identifying channels to target the potential hackathon delegates. Using anonymised data and naming from the perceived audience to create a persona. This persona is a summary of demographics, behavioral tendencies and statistics.

Each specific persona aims to represent what I know about each sector of my targeted audiences.

Personas add richness to target audiences that can help to inform key interests, likes and technology adoption. Using the persona, for example, Dreamy Designer helps to identify what engagement they would have with different types of communication. For example, Dreamy Designer, would not engage with poorly formatted PowerPoint documents as this software may not even be installed on their device(s).

🧐 Persona data capture

Using the right data to gather and to formulate a campaign for the right audience.

I have aimed to capture anonymous data about participants to facilitate requirements for social media interaction, engaging through different forms of media.

I have also captured accessibility requirements for potential delegates to enable planning for additional needs and encouraging a diverse attendance. Having diverse delegate participation will encourage ethical hacking and inclusion within teams proposed challenge solutions. Anonymising this data by abstracting photographs, avoids any ethical concerns of disadvantaging any individuals used in the study.

I have created an iconography set to capture a the accessibility requirements of potential hackathon delegates:

These icons cover visual impairment, colour blindness, hard of hearing, motor or physical difficulty, keyboard only users, anxiety, autism and dyslexia.

Example personas

User testing

and a little bit of trial and error.

User testing should take place at every possible point in the process of creating a hackathon, from asking organisers about their experiences and leaning on your own experiences, both in, taking part and organising hackathons (if you have). Testing is an integral part of an iterative design process, and its significance to establish a transparent feedback mechanism informing and driving changes throughout the creation of artefacts. The goal of user testing is to gather as much feedback as early on into the design process as possible, identifying any potential issues before spending considerable time and effort that is not detrimental to the purpose of the communication.

Testing communication concepts with potential delegates are concerned with:

❤️ Usefulness — the degree that the design achieves the goal of correctly defining the hackathon and the motivation of engaging as an attendee.

⚡️ Efficiency — the quickness with which the goal, in this case registering for the hackathon, can be achieved.

👏 Effectiveness — measured quantitatively, through interviewing, against benchmarked questions of perception and preference.

🧑🏫 Learnability — that of competently understand required commitments in attending the hackathon and establishing key messages and genre.

💃 Satisfaction — gathers feedback of perception, feelings and opinions. Engagement deepens when the users’ needs, preferences and expectations align to artefacts produced (Rubin and Chisnell, 2008).

Benchmarking

Benchmarking against the above criteria using feedback allows for consistent and recognisable feedback patterns.

This graph shows the effectiveness of each design against the total of feedback comments against each category of usefulness, efficiency, effectiveness, learnability and overall satisfaction.

Testing engagement using different platforms

Sometimes the best way to find out what works is to try a few things. I created a number of methods across different platforms of delivery to increase engagement for hackathons in general.

Podcasts

A short podcast about hackathons and my personal experiences; attending, organising and judging them.

Using my existing Podcast channel talking about hackathons and my own experiences with them. Note, if you’re planning to do a podcast with someone else make sure you get them to complete a concent form. Something like this one is great, Podcast guest release form template.

The main purpose of this podcast is to support social media campaigns with rich media accessible to different audiences and by other means, such as smart speakers and music streaming services.

Using rich media, such as Podcasts can increase engagement rates upto three times than that of text only posts (Venkatachari, 2013).

You could experiment with episodic content and a live broadcast during the hackathon itself. Podcasts are also a great way to reach different audiences over the more visual platforms of Instagram, Snapchat, Pintrest and TikTok — which are based around images and short-form videos. Remember if your images have any text on them be sure to provide alt-text. For more information about alt-text and inclusivity in social media, visit https://blog.hootsuite.com/inclusive-design-social-media/

An example tweet of the Podcast to gain interest.

Instagram teaser campaign

Different social media channels have different audiences, as such demand alternative treatments to engage their respective audiences.

According to Statista, 35% of US teens rate Instagram as their favorite social network, second only to Snapchat. In terms of gender, 43% of women use Instagram while 31% of men use it.

Instagram audience demographics (https://sproutsocial.com/insights/new-social-media-demographics/)

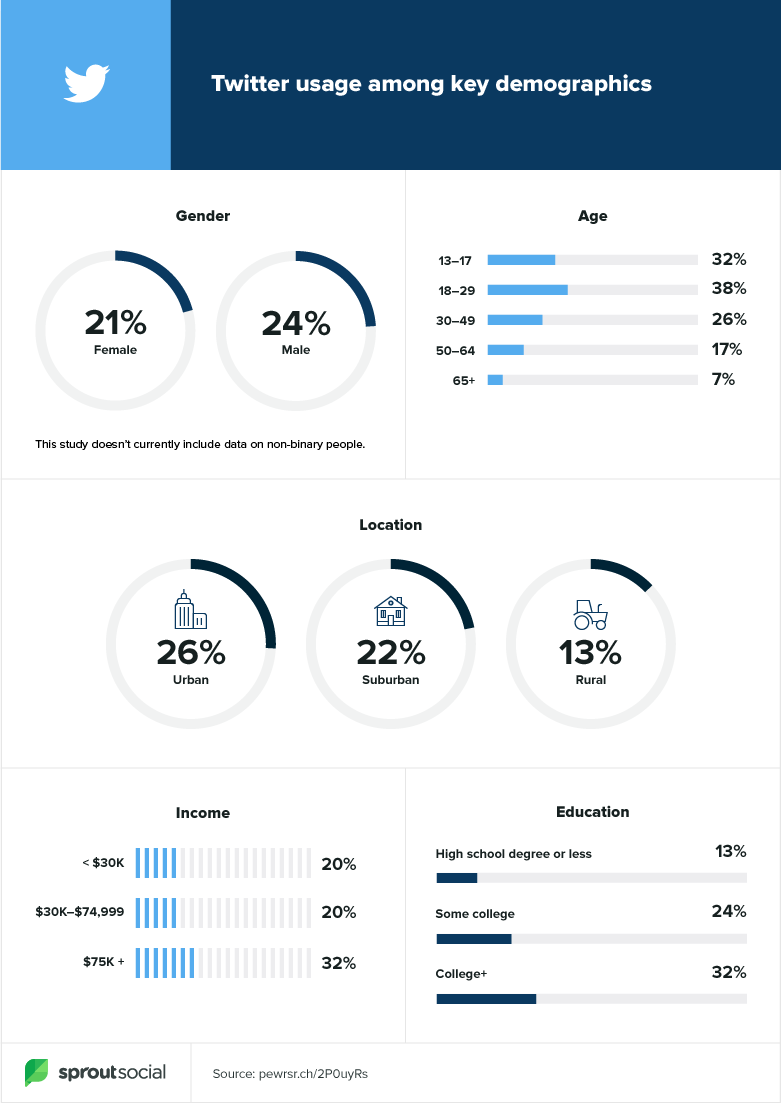

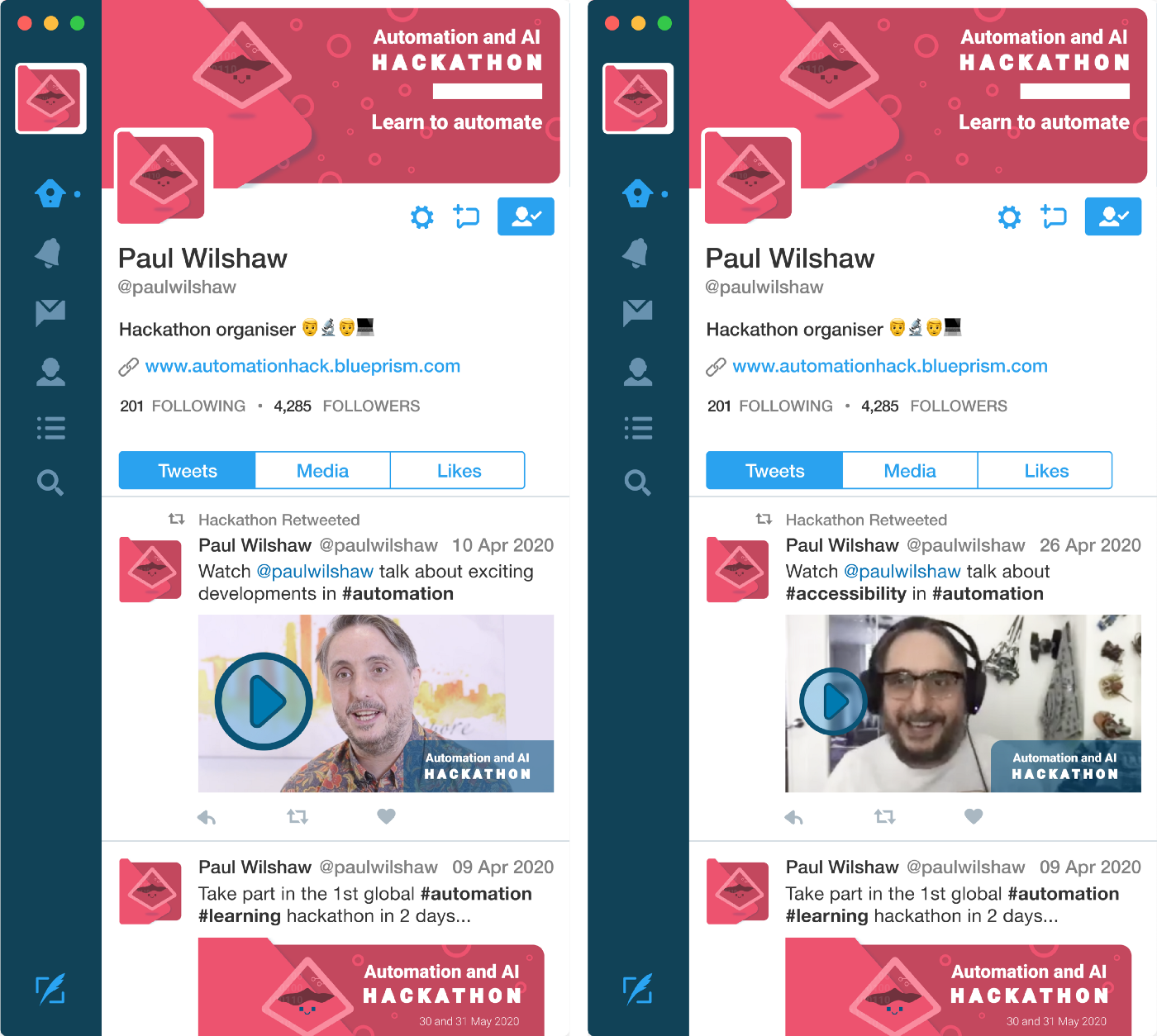

Twitter teaser campaign

The gender breakdown for Twitter users among US adults shows that 24% of men use Twitter while 21% of women use the platform. Within the platform on an international basis, the breakdown is 66% men and 34% women.

Twitter audience demographics (https://sproutsocial.com/insights/new-social-media-demographics/)

Post registration

After registering the intention is to give the attendee as much pre-event information as possible. This includes a PDF to download with how the attendees can participate in the hackathon.

Example PDF welcome pack

Getting everyone working towards a common goal.

The idea of this example hackathon is to reach a wider demographic than normal hackathons gaining insight from people who would normally be excluded from attended.

Introducing a ticketing system to reach different demographics, while raising money for the mental health charity CALM.

“Average of government health funding for mental health is less than 2%.”

Hackathon ticket pricing structure.

“The two most common mental health conditions, depression and anxiety, cost the global economy $1 trillion (USD) each year.”

Mental health is massively underfunded and under resourced, one of the many reasons to include a cost for delegate tickets.

There are three key main components to ticket pricing:

🔮 Perceived value

is what the customer thinks they will get out of your event. Here it is perception, as much as reality, that drives the transaction.

💎 The actual price

which can be greater or less than the perceived value — is what the attendee actually pays. Ideally, the actual price is as close as possible to the perceived value (without going over).

💳 Event costs

The per ticket cost to you for putting on the event — in this case business supporters would cover the cost of the event.

Value-based pricing

In the value-based pricing model, your audience is comparing perceived value of attending the hackathon and the ticket price — using a cost per ticket to determine the baseline price for breaking even (or in this case maximising charitable donations and attendee contribution).

If the attendee’s perceived value is higher than the ticket price, then the attendee will be more likely decide to purchase a ticket.

While more complex than cost-based pricing or competition-based pricing, value-based pricing allows you to design the best long-run economic model for your event. When you focus on value-based pricing. You are now aiming to deliver an event that delivers attendees a meaningful value of the ticket price. The higher the value of the ticket — the more expectations your attendees will have from the event.

There are many factors to this perception of value, such as, location, quality of service throughout the event, etc.

Limited availability

Using the strategy of limited availability and offering tiered ticket pricing can work in your favour. One tactic could be to use ‘Early bird’ tickets at a lower rate to increase early awareness and FOMO (Fear Of Missing Out) for your potential audience.

Creating premium tickets

For this event I decided to turn this principle on its head and offer premium VIP tickets to groups who are often excluded.

Eligibility to claim a free VIP ticket requires:

Delegates having claimed Free School Meals at some point in the last eight years (i.e. household income has been less than £16,190 in England or £16,105 in Scotland). (Apply for free school meals, n.d.)

Or

has been eligible for College Bursary or Education Maintenance Allowance (EMA) (i.e. household income is less than £24,421). (16 to 19 Bursary Fund, n.d.) + ambitious and willing to learn.

Using this eligibility criteria along with the VIP status gives under-represented delegates confidence to apply to attend and take part in activities.

Hackathon VIP ticket, a free and premium ticket, for delegates who may otherwise be excluded from similar events.

Tailoring experiences

Appending communication and marketing URLs with Urchin Tracking Modules (UTM), allows for tracking each social media post click to the hackathon website (Patel, n.d.). For example adding to the end of the hyperlink:

“?utm_source=medium=post&utm_campaign=learning&utm_colour=navy”

Driving experiences along different user journeys can go a long way to increase engagement.

For this example, the proposed website has a creator path and a learning path. Offering distinctions between experienced hackathon attendees and those that a new to the experience.

Example of a “Creator’ hackathon journey.

Example of a “Learning’ hackathon journey.

A critical reflection of hackathons

what could be done better (pandemic aside).

The what?

Hackathons, are a type of popular ideation contests, are events in which computer science developers, designers and sometimes individuals from other disciplines collaborate to deliver a demo or prototype that meets one of the events defined briefs (Soltani, Pessi, Ahlin and Wernered, 2014). Due to the value of hackathon outcomes, increasingly, being recognised and then applied in numerous fields with organisations, such as Facebook and Microsoft, that have become regular events for research, ideation and development (Chowdhury 2012). Hackathons have become part of the application of idea management systems. These ideation contests can often be regarded as the first phase in broader innovation processes (Cooper & Edgett 2008).

The automation and AI hackathon event is a short-term, intensive event with the focus on designing, developing and producing automation and AI prototypes or media as practical

solutions to solve the initial problem statement around mental healthcare. Preferably, aiming to include diverse expertise and experience of its delegates towards a solution. In many countries, mental healthcare services do not currently provide sustainability and involve long waits, with a quarter of patients waiting three months, to see a specialist (Campbell, 2018). Healthcare systems and institutions are still primarily based on providing acute face to face and reactionary care; this approach is not well suited to the increasing burden of mental healthcare and that of an ageing population that requires more preventative and long-term solutions.

Creating a consistent campaign to promote the hackathon over three months requires reference material to ensure suitable delegates attend the event within the intent of educating and potentially solving the problem statement, that, of finding solutions to:

Provide access to services and information for mental health patients

or

Provide information or service with specialist help to mental health patients

So what?

With a lack of funding and a higher demand for mental health services, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, China healthcare workers have reported high rates of depression (50%), anxiety (45%), and insomnia (34%) and in Canada, 47% of healthcare workers have reported a need for psychological support. A study carried out among young people with a history of mental health needs in the UK reveals that 32% of them agreed that the pandemic had made their mental health much worse (Substantial investment needed to avert mental health crisis, 2020).

A hackathon event to approach this increase in reported cases of mental health with practical and timely services seems more relevant than ever.

Even though the total cost of a hackathon can be pretty low, especially compared to other innovation processes, it does involve time and effort. Even with the best planning and preparation, the success is, primarily, measured by the quality of the outcome(s). Measuring success through levels of satisfaction, while necessary for regular events and building a recognisable brand to build attendance and public interest, is not of paramount concern. Hackathon reputation, especially to those providing the funding, is established by quality submissions where the real value will never be actualised unless they can be achieved in the post-hackathon real-world environment.

Hackathons have been successful outside of healthcare because the developer or hacker identifies themselves as the user of the product or service. In industries of retail, banking, social networking, hospitality and travel, the hacker themselves have either prior experience or easy access to the primary users, using their networks of friends and family. However, in healthcare, there is a barrier of access to users and regulations of their personal data use. Healthcare is highly regulated, and it requires a significant investment to obtain access to potential mental health patients ethically. Thus, just as large enterprises suffer from silos or separated workstreams, healthcare itself is in a silo, isolated from other domains and developments (Chowdhury, 2012). To address this, the automation and AI hackathon will provide delegates with the opportunity to perform user research with the end-users of their hackathon submission. However, this poses problems with confidentiality, data and intellectual property ownership. By gathering personas before the hackathon to approximate the end-users and then acted out by an actor or proxy at the event during the research sessions does de-risk this somewhat.

Rapid iterative mindsets of hackers at hackathons are not only applicable to ideate concepts and prototypes in computer science, but having a collaborative and interdisciplinary strategy to create successful innovative products can work for any industry. The solution is to break down the barriers between the hacker and the frontline practitioners who have problems, or pain points, to solve. Succeeding in lasting solutions involves bringing these groups together, both in the same space but one of understanding, using agreed languages and building a combined culture (Chowdhury, 2012).

Now what?

Providing mental health services has been complicated by the interruption to face-to-face services in many countries due to COVID-19. Community services, such as group therapy and one-to-one sessions have, in many countries, been unable to meet in-person for several months (Substantial investment needed to avert mental health crisis, 2020).

Access to research potential user or frontline practitioners has also lessened as services have been disbanded or decentralised. A change in how mental health treatment is accessed could result in a change in the solutions to the hackathon problem statement if it is still valid. The information used to generate end-user personas and user research data may change in response to social distancing. A decentralised mental healthcare service could provide its own solutions and problems over time.

Demands for reliance on technology support for delegates from skill and economically deprived areas can be approached in a formal face-to-face hackathon event, where hardware and software can be supplied with support. Virtually, however, this is much harder to achieve, as requirements for entry are much higher with each delegate having to provide broadband, continuous access to a laptop or desktop computer (with the minimum technical specification) and pre-installed software during the entire event.

A problem not only posed by this hackathon but for further investigation as COVID-19 has accelerated many organisation digital transformations.

The hackathon can proceed virtually. However, the diversity and inclusion reasoning would have to change as providing equipment and one-to-one support would be a lot harder to support in these unprecedented times.

References

Campbell, D., 2018. Delays In NHS Mental Health Treatment ‘Ruining Lives’. [online] the Guardian. Available at: <https://www.theguardian.com/society/2018/oct/09/mental-health-patients-waiting-nhs-treatment-delays> [Accessed 9 May 2020].

Chowdhury, J., 2012. Hacking Health: Bottom-up Innovation for Healthcare. Technology Innovation Management Review, [online] 2(7), pp.31–35. Available at: <https://search.proquest.com/docview/1614473182?pq-origsite=primo> [Accessed 19 May 2020].

Consultancy.uk. 2015. Innovation Failures Cost UK Companies 65 Billion A Year. [online] Available at: <https://www.consultancy.uk/news/2525/innovation-failures-cost-uk-companies-65-billion-a-year> [Accessed 19 May 2020].

Finextra Research. 2013. Barclays Takes The Crown At Digital Wallet Foundry. [online] Available at: <https://www.finextra.com/newsarticle/24664/barclays-takes-the-crown-at-digital-wallet-foundry/developer> [Accessed 16 May 2020].

Folz, R., 2015. Selling Out And The Death Of Hacker Culture. [online] Medium. Available at: <https://medium.com/@folz/selling-out-and-the-death-of-hacker-culture-fec1f101b138> [Accessed 16 May 2020].

GOV.UK. 2019. English Indices Of Deprivation 2019: Mapping Resources. [online] Available at: <https://www.gov.uk/guidance/english-indices-of-deprivation-2019-mapping-resources> [Accessed 19 May 2020].

GOV.UK. 2020. 16 To 19 Bursary Fund. [online] Available at: <https://www.gov.uk/1619-bursary-fund> [Accessed 17 May 2020].

GOV.UK. n.d. Apply For Free School Meals. [online] Available at: <https://www.gov.uk/apply-free-school-meals> [Accessed 17 May 2020].

Jee, M., 2015. CV Driven Development (CDD). [online] Martin Jee’s blog. Available at: <https://martinjeeblog.com/2015/03/11/cv-driven-development-cdd/> [Accessed 18 May 2020].

OpenDataCommunities.org. 2019. Indices Of Deprivation 2015 And 2019. [online] Available at: <http://dclgapps.communities.gov.uk/imd/iod_index.html#> [Accessed 19 May 2020].

Patel, N., n.d. The Ultimate Guide To Using UTM Parameters. [online] Neil Patel. Available at: <https://neilpatel.com/blog/the-ultimate-guide-to-using-utm-parameters/> [Accessed 17 May 2020].

Postigo, H., 2012. The Digital Rights Movement: The Role Of Technology In Subverting Digital Copyright (The Information Society Series). Cambridge: MIT Press, p.177.

Richterich, A., 2017. Hacking events: Project development practices and technology use at hackathons. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, 25(5–6), pp.1000–1026.

Rubin, J. and Chisnell, D., 2008. Handbook Of Usability Testing. Indianapolis, IN: Wiley Pub.

Soltani, P., Pessi, K., Ahlin, K. and Wernered, I., 2014. Hackathon — a method for Digital Innovative Success: a Comparative Descriptive Study. In: 8th European Conference on IS Management and Evaluation ECIME 2014. [online] Ghent: University of Ghent. Available at: <https://www.researchgate.net/publication/265841848_Hackathon_-_a_method_for_Digital_Innovative_Success_a_Comparative_Descriptive_Study> [Accessed 19 May 2020].

Venkatachari, D., 2013. Rich Media And Social Media: A Match Made In Marketing Heaven — Clickz. [online] ClickZ. Available at: <https://www.clickz.com/rich-media-and-social-media-a-match-made-in-marketing-heaven/40581/> [Accessed 17 May 2020].

Who.int. 2020. Substantial Investment Needed To Avert Mental Health Crisis. [online] Available at: <https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/14-05-2020-substantial-investment-needed-to-avert-mental-health-crisis> [Accessed 19 May 2020].

Who.int. n.d. Mental Health. [online] Available at: <https://www.who.int/health-topics/mental-health#tab=tab_2> [Accessed 19 May 2020].

Zukin, S. and Papadantonakis, M., 2017. Hackathons as Co-optation Ritual: Socializing Workers and Institutionalizing Innovation in the “New” Economy. CUNY Academic Works,.